Open Source Urban Housing for the Caribbean using Roman inspired design

The Roman empire in its peak glory had figured out a few things that modernity is still catching up on. Monuments such as the colliseum still stand because of special concrete that we only just now re-discovered how to make. They had also figured out a number of important important urban housing principles we seem to have forgotten. This project seeks to learn from the their wisdom, particularly around the Roman Domus and its free air conditioning.

Volunteer opportunity: This in-process architecture collaboration by engineer Andrew Malone extends the open source housing design toolkit from the Open Building Institute (an Open Source effort to make ecological and affordable housing widely available), to create eco-compatibile ancient Roman inspired designs to enhance urban housing comfort and safety in lower income hurricane prone carribean countries, such as Hati, Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, as well as to consider and apply the principles of urban design for new developments.

Architect Statement

My wife and extended family are from the Dominican Republic and I noticed that many warm climate areas could be using ancient traditional approaches to urban housing to make it much more comfortable, secure and sustainable. I seek to address some the following common shortcomings

- Low quality construction in Caribbean urban landscapes

- Lack of sustainable and culturally relevant building designs

- Need for hurricane resistant, water contamination resistant and socially defensible residences

- Preservation/re-introduction of local heritage through architectural and urban design

Project or Program Description

- Project Objective: Complete the architectural design, structural engineering, mechanical engineering, equipment selection & specification, and hard cost estimate required to construct an affordable, environmentally sustainable urban mixed-use prototype villa that can be unitized as an urban fabric building for warm climate communities. Particularly focused on the Caribbean Islands.

- Methods and Approach:

- Research and analysis of the Roman Domus and its adaptation to Caribbean climate and culture

- Design and development of a prototype building design that integrates Roman and Caribbean architectural elements

- Evaluation and assessment of the prototype's cost/energy performance and community impact

- Collaboration with a structural engineer and architect to incorporate low cost open source plan set that can be legally built in the Spanish Caribbean

- Selection of a suitable site in a Caribbean city for the prototype construction (Ref: Old San Juan and Culebra Island)

- Deliverables

- Research and Analysis Summary

- Structural Engineering & Architecture plan and specification set

- Contributing files to add to the Open Building Institute toolkit library: https://www.openbuildinginstitute.org/library

- Creation of a digital model using Open Source design software: https://www.sweethome3d.com

- Future plan for live energy and environmental assessment of a constructed prototype's electrical & water usage performance as well as actual carbon cost of construction

Appendices

Research for the project is based initially on the corpus of documents referenced in the appendix.

- The Roman Domus as a Caribbean Urban Housing Solution - Andy Malone

- The Original Green - Steve Mouzon

- Smart Dwelling - Steve Mouzon

- A Living Tradition - Steve Mouzon

- Architecture For The Poor - Hassan Fathy

- Mass Wall Masonry, Vaulted Floors and Stairs Structural Engineering - John Ochsendorf, Matthew DeJong & Philippe Block

- How to Build a Small Town - Wrath of Gnon

- Using Models of Historic Towns as Templates by @WrathofGnon

- Duplication Through Replication - Leon Kreir

- A Town Well Planned

Appendix A

The Roman Domus as a Caribbean Urban Housing Solution

Blog Post by Andrew Malone, Wednesday, August 3, 2016

https://andrewmalone.blogspot.com/2016/08/the-roman-domus-as-caribbean-urban.html

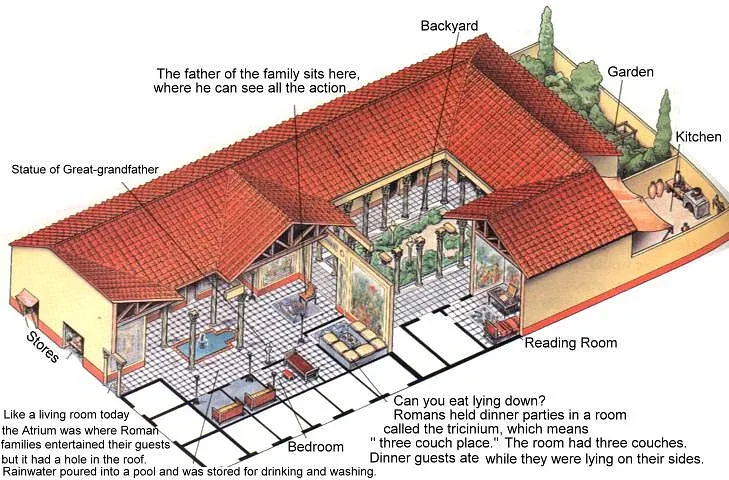

I've been on a bit of a kick right now learning about the Roman Domus; an ancient urban housing solution from about 2000 years ago. It all started with a simple question. Why do they have a pool of water (impluvium) in the center of the living room (atrium) like that?

Well, it turns out that the impluvium is a much more functional feature than I realized. It's actually a remarkable rainwater collection, storage and home cooling device all in one. If you're looking for the best sustainability solutions, and I think we all should be, it makes a lot of sense to look to the past. To a time when fossil fuels were still locked in their original state and people had to make every day human life work without them. Once we've scoured the past for amazing resource saving ideas, then by all means fire up your gas oven or take a flight halfway around the world. Let's use our resources to their highest and best purpose.

In this post I’ll address timeless issues, like rainwater collection, greywater systems, passive cooling, sustainable finance, and suggest some modern layout improvements to the domus for use in our lives today.

In short, ancient Romans collected rainwater from their roofs, filtered it through a sand filter and stored it in a subterranean cistern for later use in home cooling and cleaning. All for free. Let’s look at how we might reap some of the same benefits from clever design today. According to this handy Reddit thread:

Households usually collected their own rainwater from the roof to supplement aqueduct supply. The first rains would be allowed to run off the roof into a basin (impluvium) in the atrium of the house, and out through a drain into the street. Once the rain had washed the roof clean, the drain to the street was stopped-up, and another hole in the impluvium basin was opened to allow clean rainwater to fill the cistern. Usually the cistern mouth had a sediment trap on it as well, so that only clean rainwater would get into the holding tank.

Like so:

Followed by Wikipedia’s description:

Inspection (without excavation) of impluvia in Paestum, Pompeii and Rome indicated that the pavement surface in the impluvia was porous, or that the non-porous stone tiles were separated by gaps significant enough to allow a substantial quantity of water caught in the basin of the impluvium to filter through the cracks and, beyond, through layers of gravel and sand into a holding chamber below ground. The circular stone opening (visible in the photograph, resembling a chimney pot) allows easy access by bucket and rope to this private, filtered and naturally cooled water supply. In wet seasons, excess water that could not pass through the filter would overflow the basin and exit the building, and any sediment or debris remaining in the surface basin could be swept away.

In hot weather, water can be drawn from the cistern chamber (or sourced from municipal supplies outside the domus) and cast into the shallow pool to evaporate and provide a cooling effect to the entire atrium. As the water evaporates, the surrounding air is cooled and becomes heavier and flows into the living spaces and is replaced by air drawn through the hole in the ceiling above (compluvium). The combination of the compluvium and impluvium formed an ingenious, effective and attractive manner of collecting, filtering and cooling rainwater and making it available for household use as well as providing cooling of the living spaces. (emphasis added)

In modern times, the manual labor used to draw water from the cistern would be replaced by pumps and the water itself could be sent to toilets and irrigation or could be treated and used to supplement or replace the city system (which is usually not 100% potable anyway).

Here are a couple more images of the atrium, compluvium and impluvium set up. The walls of the house are made of rubble mass wall masonry covered with painted plaster and sometimes stone or tile. The floor is also a stone or mosaic floor. The roof supported by wooden beams set into masonry pockets is slanted inward and features a ceramic tile roofing system with gutters and drain spouts from the four corners of the compluvium to direct rainwater into the center of the impluvium.

Since the atrium is exposed to seasonal weather changes, this system doesn’t make sense in temperate zone climates, but is ideally suited to tropical and sub-tropical zones. Looking at the typical climate in Pompeii where some of the best examples can be found I discovered that original Roman Mediterranean climate would have been slightly cooler, but not unlike the Deep South and Caribbean.

My wife is Dominican and we spend a fair amount of time in Santo Domingo, the oldest colonial city in the Americas. The Zona Colonial has a lot of really wonderful architecture,

and some of it even follows a loosely similar concept with interior courtyards and pools

Historic Landmark Hotel Doña Elvira

But the average house built over the last 50-70 years looks a lot like the examples below.

In most of the Caribbean it is quite common to live the entire year without air conditioning. Since it’s an island, the cost of electricity is high and once you become accustomed to the heat it’s bearable but not always comfortable. The rain is frequent, but usually pleasant and warm. Also water service is occasionally interrupted and the tap water is not always potable. It is wise to boil or filter city water before consumption. As local water systems age and the equipment to treat your own water drops in price, this may increasingly become the norm. In Santo Domingo burglary is (increasingly less of) an issue so most families put bars on their windows and balconies to keep out intruders.

Let’s take a look at the total floor plan for a typical domus.

You’ll notice the Roman domus has a few other advantages. The whole house is inwardly focused and places windows and potential 2nd floor balconies on the inside away from possible burglars. Also, because the streets would have been filled with people and animals, they were noisy and polluted. The Romans built their homes with street facing retail only reserving a single entrance door for themselves. These retail spaces helped to pay for the costs of the house and served the public interest. Today, it is easy to imagine creating a second floor above the retail spaces for live-work units that pay for the main house.

The central room (#5 tablinium) served as the meeting place for the house. It was the focal point and divided the public space in the atrium from the private space in the garden-court (#14 peristylium).

As a possible solution to urban housing in the Caribbean the Roman Domus would provide an excellent solution. In the Dominican Republic, they reserve their front yard primarily for the automobile anyway. It would be simple to re-purpose the two commercial spaces in the Roman design for a street facing garage that could eventually be converted to retail space in the event that the family needs the income or prefers to use taxis and transit. The need for security is similar to the Roman situation and providing bars on the roof over the compluvium and at the perimeter of the peristylium is an option.

Below, I’ve re-imagined the uses in a modern floor plan. Doing away with the traditional office-like tablinium and replacing that with an open kitchen. The meeting place of our modern lives. The kitchen I envision would have two mobile workstations on castors (shown in grey) that could be configured as service and prep islands or as casual dining and conversational surfaces. A second floor could be easily added for additional living space or to rent to the shopkeepers as supplementary income. The impluvium with cistern would remain and the collected rainwater could be used as grey-water to power toilets and irrigation or could be treated in a water treatment closet and used throughout the house. Adding electrical battery storage first and solar power cells second would enable the house to operate almost entirely off grid and would avoid any disruptions in service common on the islands. The garden could be edible or just a simple yet elegant backyard surrounded by covered walkway. As a typical fabric building, these homes meet most of the tests diagrammed in Steve Mouzon's exceptional work on the Smart Dwelling.

It is typical in the region to build the home structure with poured concrete columns/beams, the walls constructed of concrete block and plaster, and clay tile roofs. That is actually very similar to the traditional Roman construction and the added mass makes sense to help keep the house cool and durable. Even the heaviest rains can simply be wiped off the stone or ceramic flooring and masonry walls.

In a country with high energy costs and a favorable climate this system could make the interior of modern homes much more comfortable and solve several other major issues with typical Caribbean urban architecture.

Appendix B

The Original Green

Book by Steve Mouzon, 2010

Synopsis from the companion website: https://originalgreen.org/

Originally, before the Thermostat Age, the places we built and buildings we built had no choice but to be green, otherwise people would freeze to death in the winter, die of heat strokes by summer, starve to death, or other really bad things would happen to them. Today, as we are working to re-learn how to live sustainably, much of the focus is on the gadgetry of green: Gizmo Green. This notion that we can simply invent more efficient mechanisms, and throw in some bamboo to boot, is only a small part of real sustainability.

So this is what the Original Green makes... sustainable buildings in sustainable places... but what is it, really? The Original Green is the collective intelligence behind those places. In common terms, it’s the sustainability all our great-grandparents knew by heart.

The operating system of the Original Green is something called a Living Tradition; it spreads the wisdom of sustainability in ways vaguely similar to how nature spreads genetic material. Living Traditions bear about as much resemblance to an historical tradition as a living creature does to a fossil. One is alive, while the other is not. With that having been said, preservation is the act of ongoing sustainability, because how can we live sustainably if we keep throwing places and buildings away?

The best living traditions are held by the public at large, rather than just a few people. And if a living tradition is to produce sustainability, it must involve everyone. Our behavior must improve, or our machines can’t save us. In short, there’s something for everyone to do. And while Gizmo Green solutions are hurt by economic downturns, Original Green measures fare much better, because most of them operate naturally.

Appendix C

Smart Dwelling I & II

Blog Series by Steve Mouzon, 2009

Table of Contents

- WSJ SmartDwelling

- The Tower of Wind & Water

- Breeze Chimneys

- Sideyard Sail

- Laundry Eave

- Green Walls

- Kitchen Garden

- Windows & shutters

- Invisible Things

- SmartDwelling II

The Wall Street Journal on SmartDwelling I

https://originalgreen.org/blog/2009/the-wall-street-journal-on.html

Monday, the Wall Street Journal ran a story on The Green House of the Future, which featured designs by four architects: William McDonough, Rios Clemente Hale, Cook + Fox, and myself. My design, SmartDwelling I, is pictured above... the previous post and several of the next ones will focus on aspects of the house that contribute to its sustainability.

The Journal article created a lot of buzz this week... Twitter had too many tweets to count, and the blogosphere was loaded with references, too. Green Building Advisor was one of the first to pick up the story, as was Treehugger. Jetson Green has a poll where you can vote for your favorite of the four designs... scroll down to the bottom of their article to vote. Fast Company commented on the designs, as did New West, which appreciated the focus on smaller designs. I don’t know about the other designs, but SmartDwelling I has only 1,200 square feet of conditioned space, and yet houses three beds and two baths. Its interior contains numerous space-saving innovations which I’ll cover in another post.

The New Regionalist was very emphatic on his preference among the four designs. PlaceShakers and NewsMakers devoted their entire post on the 27th to SmartDwelling I, and the Mother Nature Network singled out SmartDwelling I for praise. The Washington Post reacted negatively to the Journal article, pointing out that our first priority must be to reshape our neighborhoods. Too bad they didn’t realize that SmartDwelling I was specifically designed for an urban lot (40’ x 100’) that is served by a rear lane or alley. In short, it works in many infill conditions, or in creating new New Urbanist neighborhoods. The Huffington Post indicated that it was one of their most-read and most-commented-upon green stories this week. Planetizen, Businessweek, CNU New England, ArchNewsNow, and a number of others also picked up the story.

Here are some SmartDwelling I ideas that didn’t make it into the Wall Street Journal article, but which you might find useful: My design is consistent with the objectives of the New Urban Guild's Project:SmartDwelling, which will produce highly sustainable homes for the major regions of the US. Regional issues are crucial to sustainability: climate, regionally available materials and skill sets, occasional regional atmospheric (hurricanes, etc.) and geologic (earthquakes, etc.) events, and culture. Because this is the first house designed explicitly on the SmartDwelling Project principles, I'm calling it SmartDwelling I; it is designed for the Gulf Coast region. I founded the Guild nearly a decade ago; today, it consists of 65 New Urbanist architects and designers.

SmartDwelling I includes a number of inventions, such as the double-cranking windows & shutters to channel breezes, the Breeze Chimneys and Sideyard Sail (based on the nautical heritage of the Gulf Coast,) the Green Shed, the Cool Dip, the Laundry Eave, the Curtain Columns, and a number of interior innovations. But the primary design criteria wasn't "Is it new?" but rather "Can it work?" This means that some things need to be invented to solve today's problems. Our ancestors never had to worry about generating electricity, for example. Other things, such as the shape of the roof, have been demonstrated for centuries to be the most durable. So this home is neither historical nor futuristic; rather, it is pragmatic, because it is based on things that work best in the long run.

WSJ on SmartDwelling I - The Tower of Wind & Water

https://originalgreen.org/blog/2009/wsj-on-smartdwelling-i--.html

This morning, the Wall Street Journal ran a story on The Green House of the Future, which featured designs by four architects: William McDonough, Rios Clemente Hale, Cook + Fox, and myself. My design, SmartDwelling I, is pictured above... the next several blog posts will focus on aspects of the house that contribute to its sustainability.

The Tower of Wind & Water is the central feature in the top image. Here’s a closer view. Rainwater is collected around the entire house in gutters, then runs to either side of the tower where it burbles into conductor heads that channel it into the Rain Pool, celebrating the arrival of new rainwater with sight and sound. The Rain Pool is the boundary between the Hearth Garden from the Kitchen Garden.

Rainwater is then pulled up as needed out of the Rain Pool to the cistern, which is the round part of the tower. Elevating the cistern allows water to gravity-flow from there to anywhere on the main level, where it can be used for irrigation or other greywater uses.

The top element of the Tower of Wind & Water is a wind generator that produces electricity. Nobody makes this exact shape of wind generator yet... many of the current generation of generators look as if they were engineered but not designed, leaving them inherently unlovable. This one, on the other hand, does its best to be beautiful while it is generating your electricity. The ground level of the Tower of Wind & Water contains all of the alternative energy equipment for the house.

Breeze Chimneys

https://originalgreen.org/blog/2011/smartdwelling-i---breeze.html

There's much more to SmartDwelling I than the things I wrote about two years ago when it was published in the Wall Street Journal's Green House of the Future story. Really cool stuff is afoot with Project:SmartDwelling, so this will be the first of several new posts looking at SmartDwelling elements.

SmartDwelling I with the two breeze chimneys at the top

top view of Breeze Chimney

There are two Breeze Chimneys on SmartDwelling I, which was designed for the US Gulf Coast region. Because it's a land by the sea, I decided to use seafaring materials for the Breeze Chimneys. As we'll see in a moment, Breeze Chimneys in other parts of the country could be made out of other materials like sheet metal. The framework is built of small spars, like those which frame sails on sailboats. The spars could either be made of wood or fiberglass. The shroud is sail cloth stretched over the spars. This assembly is attached to a ring at the top of the chimney that rotates freely. Here's how it works:

section through Breeze Chimney showing air flow

The Breeze Chimney is designed to turn into the wind, like a weathervane. The open end of the Breeze Chimney is always leeward as a result. There's a phenomenon in physics known as the Venturi Effect, and it works like this: air moving past an opening tends to pull gases or liquids out of the opening. If you're old enough to remember cars before fuel injection, then it was the Venturi Effect that made the carburetors work.

Breeze chimneys behave the same way. They have another thing working for them as well: the Thermal Chimney Effect. Because hot air rises when given the opportunity, hot air in a tube like a chimney flue will rise out of the tube, pulling other air in behind it from the room below. To start a breeze chimney, all you need to do is to open a window somewhere in the house.

Pulling in air almost as warm as the air exhausted by the Breeze Chimney wouldn't do much good, so you need to find a window around the house or shop where the air is coolest.

The best place would be under a grove of trees or big shrubs. Not only do the leaves shade the area around the window, but they also cool the air even further by giving off water vapor. It can easily be 10-15 degrees cooler under a shady grove or in a thicket.

A louvered verandah like the ones found throughout the Bahamas would be good because the louvers prevent the sun from getting into the porch and warming it up. A porch on the shady side of the house would work equally well.

A breeze chimney works best in late afternoon or early evening, when the air has cooled a bit from the heat of the day. Porches on the eastern side of the building would be coolest at this time of day. There's no reason you have to use the same window, however… you could experiment to see what works best for you. But in any case, it's the act of opening the window that starts the Breeze Chimney's operation because without replacement air pulling into the house, the Breeze Chimney can't pull air out. So think of it as an attic fan that doesn't require any electricity.

side view of breeze chimney

What about storms? Wouldn't the sail cloth tear in high winds, flooding the house? Clearly, there needs to be some way of shutting the Breeze Chimney in a storm, or when you're going to be away from home for awhile. See the heavy black line on the right side of this drawing? It's meant to represent a spring metal arc that holds the spars up. There would be two cords coming down the chimney. Pull one of the cords, and that pulls the spring metal arc over to the left, collapsing the shroud. Pull the other one, and it pops back up. I haven't yet built a Breeze Chimney, so I'm sure it would require a bit of tinkering, but that's the general idea of how it should work.

The house above was designed for a competition we never expected to win. It was intended as a critique of the Gizmo Green competition program and, just as I expected, the jurors didn't view it very kindly. I'll blog more about it later… my point of showing it here is to illustrate how differently Breeze Chimneys can be designed.

This house was designed for Dallas. A century ago, you could find pivoting sheet metal roof vents all over the Midwest and Southwest. So I designed this Breeze Chimney to be built of the same material. There are only two differences between this Breeze Chimney and the old pivoting roof vents. First, it's a good bit larger than the old ones so it can ventilate the whole house. Second, the old pivoting roof vents usually vented the attic. In this design, there's a chimney (concealed by the roof) that connects the cap to the living spaces below.

SmartDwelling I - Sideyard Sail

https://originalgreen.org/blog/2009/smartdwelling-i---sideyard.html

SmartDwelling I, published recently by the Wall Street Journal in their Green House of the Future article has a number of innovations that aren’t so much inventions as they are re-purposing things we’ve known about for a very long time. Green Walls are one such pattern; the Laundry Eave is another.

SmartDwelling I was designed for the Gulf Coast, where there is a nautical heritage, as the early towns and cities were all built with a direct dependence on commerce across the Gulf. So when I started looking for a way to catch breezes coming down the street and redirect a portion of the breeze through the sideyard, a sail was an obvious choice.

The Sideyard Sail can be furled in a storm, of course, in order to protect the sail cloth... and also to avoid sending high storm winds through your side yard. It works by pivoting a boom out over the frontage garden. If there is no frontage garden, then the front garden wall should be made tall enough (this one is) so that the boom is above head height. But that’s OK... that simply assures a private side garden.

Incidentally, the original Sideyard Sail was envisioned for Schooner Bay, a wonderful new town in the Bahamas, on the eastern shore of Abaco. It will be a working fishing village. It has organic farms on its western border, so that you can look out over the fields and over the waters from which much of your food comes. Because of this, Schooner Bay will be one of the first new Nourishable Places to be built in recent times. Schooner Bay will also build upon all other foundations of the Original Green, making it one of the first Original Green places to be built in our time.

The first Original Green place to be designed was Sky, located in the Florida panhandle. It is now in the development approvals process, and should be under construction shortly. Sky is a veritable laboratory of Original Green ideas, breaking new ground in too many ways to count. See the Sky Method (it’s a big file; give it a few to download) for a highly organic and sequential land development method invented for Sky. It promises to bypass the normal development brain damage of millions of dollars of infrastructure investment up front before you can sell a single lot... brain damage that is actually almost impossible since the Meltdown, because banks have basically quit loaning money for new development.

SmartDwelling I - Laundry Eave

https://originalgreen.org/blog/2009/smartdwelling-i---laundry.html

SmartDwelling I, published recently by the Wall Street Journal in their Green House of the Future article has a number of innovations that aren’t so much inventions as they are re-purposing things we’ve known about for a very long time. Green Walls are one such pattern; the Laundry Eave is another.

If you don’t want to pay to electric-dry your clothes, then there are currently two common choices. The European method is to hang them on pulley-driven clothes lines over the street. Neighbors therefore know if it’s boxers or briefs, and that seems like a little too much information.

The American method is to put up a couple posts with frames on top in the back yard, and string the clotheslines between them. Problem is, as any kid knows who has spent any reasonable amount of time playing in such a back yard, running into such a clothesline while going for a fly ball or a pass can nearly take your head off, because they’ll catch you under your chin, holding your head in place while the rest of your body goes flying underneath. This is such a common phenomenon that it spawned a term in American football: “Getting clotheslined” means getting tackled by a defender who holds his arm out at neck level, just like the clothesline... leaving you to crash bone-jarringly flat of your back a moment later.

The Laundry Eave solves both of these problems. It uses the pulley, like in Europe, so that you can hang clothes out of any window on any floor of the building. But it is placed on the back or side of the building so your undies aren’t hanging out over the street.

The last element is a very deep bracketed eave that hangs over the entire clothesline, so that a shower that comes up while the clothes are drying don’t soak them all over again.

Why might you want to air-dry rather than electric-dry your clothes? The energy savings are obvious. And if you’re brave enough to commit to doing it all the time, then you don’t even need to buy a dryer. That also saves on electrical costs... at the very least, you don’t need the circuit, the wire, and the outlet. But because a clothes dryer is a big electrical load, eliminating the dryer just might make the difference in being able to go down to a smaller service. One other thing on electrical service... if you make your own electricity with photovoltaic panels, then eliminating the dryer may save a really nice chunk of change by requiring fewer photovoltaic panels. And finally, three more reasons that everyone can enjoy... air-dried clothes usually smell fresher than electric-dried ones, they’re not full of static electricity, and the clothes actually last longer!

SmartDwelling I - Green Walls

<https://originalgreen.org/blog/2009/smartdwelling-i---green.html>

SmartDwelling I, published recently by the Wall Street Journal in their Green House of the Future article has a number of innovations that aren’t so much inventions as they are re-purposing things we’ve known about for a very long time. Green Walls are one such pattern. The idea is really simple: take all building or garden walls within easy harvesting reach (say, up to 8’ tall) and plant them. The Green Walls to the left in the image above are planted against a masonry garden wall, while the Green Wall to the right is planted against the garage. And no, all those green boxes aren’t finely-clipped hedges... that’s just the closest I could get with Sketchup. This is a normal raised-bed vegetable garden.

How do you plant a Green Wall? Well, we eat fruits and a few vegetables that grow on perennial plants like fruit trees, while most vegetables grow annually: you plant them in the spring and they die in the frosts of the fall. Because annuals like fruit trees grow for many years, they can typically grow taller than annuals like onions or rhubarb. Many vegetables will never make it to the top of the wall, so the top should be reserved for perennials.

There’s an ancient art known as espaliering where fruit trees are trained tight against a wall. They never get anywhere near as large as they would growing in the wild, but they produce an amazing amount of fruit for such a tiny footprint. The tops of Green Walls are composed primarily of espaliered fruit trees.

See the lighter green below the espaliered fruit arches? That area is reserved for vegetables. Vining ones (such as beans and peas) work best. It’s not shown here because it would be largely hidden, but the area below the arch has a lattice built of pruned branches (gotta recycle, you know?) attached to the wall. Vegetables growing in this area would vine up the lattice.

Some vining vegetables don’t work so well... until now... because their fruit is so heavy. Several types of melons fit this description. No problem... SmartDwelling I envisions Melon Cradles which would be hung from the lattice when fruit sets on in the springtime, carrying their weight as they grow.

There’s a lot more to Green Walls, some of which you can read here. As you will see, they actually weren’t my idea, but rather, Julie Sanford’s. And the principles, of course, have gone back thousands of years... we’re just applying them in a certain way. You’ll also note that I was calling them Wall Gardens at the time... might even go back to that term. What do you think? Wall Gardens? Green Walls? Which is a more descriptive and more enticing term?

SmartDwelling I - The Kitchen Garden

https://originalgreen.org/blog/2009/smartdwelling-i---the-kitch.html

The Kitchen Garden is the one part of SmartDwelling I that a few people look at and say “you can’t be serious!” For them, buying food at the grocery store is simply too ingrained in their version of modern life to ever consider raising any appreciable portion of their own food. And make no mistake about it... the areas devoted to food in SmartDwelling I would likely provide most, if not all, of the food needed by a family of three or four for an entire year, assuming you used the space efficiently.

How is this possible? Doesn’t the American agricultural system require an acre or two of land (depending on where you are and how long the growing season is) to provide food for just one person? And haven’t we always known that the American agricultural system is the most efficient on earth?

Here’s the problem. America’s industrial food system is the most efficient on earth, so long as you’re measuring the man-hour efficiency of the guys on the tractors. One person on a mega-tractor as tall as a two-story house can probably work a thousand acres or more in a single day. Meanwhile, one person growing food in bio-intensive fashion has a hard time tending more than a single acre. But that guy on the mega-tractor is only a tiny part of the supply chain. Getting food to market requires truck drivers to take it to the processing plant, workers in those processing plants that break it down into its food-chain parts (high fructose corn syrup, etc.) more truck drivers to take it to assembly plants where more workers turn it into soda, Chicken McNuggets or whatever, more truck drivers to take it to the distributors who hire even more truck drivers to take it to the grocery stores. Is this starting to sound like more oil than food? It is. According to Michael Pollan, delivering a single calorie of highly-processed food (most of the stuff America eats) requires 70 to 90 calories of gasoline! And this doesn’t even take into account all the people working for the processors and the people working for the food manufacturers... who also must, by the way, buy even more gas to get to work in their corporate office parks. So the efficiency of the guy on the tractor (which can cost a million dollars or more, and must be manufactured by lots of employees at John Deere, etc.) is completely an illusion.

The bio-intensive farmer, on the other hand, while tending only an acre, can take their produce to a nearby farmers’ market or sell it to local restaurants, reducing the food chain to just one person in a truck. And the food chain, rather than stretching across national boundaries, can be as short as 20-30 miles or less.

So while the man-hour efficiency of the industrial food chain is a complete illusion, the acre efficiency of bio-intensive gardening is completely real. Remember that one person working hard to tend one acre? Well, they’re not just feeding one person (or less) on that one acre like the industrial food system would do. Rather, depending on growing season and local conditions, that one acre can easily feed twenty people or more... and that’s without going to some of the extremes (like Green Walls and Melon Cradles) that SmartDwelling I includes. That’s real efficiency... one person feeding twenty people or more... and with only a tiny fraction of the appetite for gasoline that we find in the entire industrial food chain.

So beyond the fact that it’s highly acre-efficient, what’s so cool about the Kitchen Garden in SmartDwelling I? Lots of things. See the pool in the center? That’s a Tilapia Pool. Tilapia thrive in incredibly tight quarters... there can be more tilapia than water in a pool and they’ll do just fine. So you can think of it as a water feature, or as a big protein machine... take your pick. You’ll also notice a few chickens running around. Those are the hens that inhabit the henhouse under the stairs to the apartment/guest room/kids’ room/office/studio/workshop/whatever over the garage. You only need a few hens to eat garden pests, provide a continuous supply of fertilizer... and also a continuous supply of eggs for even more protein.

You’ve probably noticed that the vegetables grow in raised beds. Rather than single rows of plants 2-3 feet apart like industrial tractor farming requires for most crops, raised beds grow vegetables much more compactly. They’re limited only by the reach of the person tending the beds... a three-foot bed allows you to easily work the middle of the bed from any edge without bending over much, if at all.

You likely also noticed the Green Walls all around the garden. Actually, this drawing hides the near Green Wall so you can see the entire garden. but in any case, the entire garden is surrounded with Green Walls, which are highly efficient for reasons I blogged about earlier.

But this isn’t just a place to work. See the two little structures with tools handing on the lattice walls, and seats inside? The one on the right is the Morning Pavilion. That’s where you go and sit and watch the mist rising off the garden in the early mornings, maybe with a cup of coffee... and with the morning sun streaming in over your shoulder. The one on the left is the Evening Pavilion. You can sit there at the end of a day of gardening, admiring your hard-won handiwork, with the evening sun streaming in over your shoulder again, just as it did in the mists of morning.

SmartDwelling I - Windows & Shutters

<https://originalgreen.org/blog/2009/smartdwelling-i---windows-.html>

SmartDwelling I has the distinction of being the only one of the four houses published recently by the Wall Street Journal in their Green House of the Future article that could be built today. Or at least 98% of what was shown can currently be built. One of the few exceptions are the windows and shutters. That might be about to change.

Casement windows are easier to make airtight than double-hung windows because the sash squeezes the weatherstripping tight to the frame when the window closes instead of sliding along the surface of the weatherstripping like double-hung sashes must do. But casements have a problem: If you’re in a region like the Gulf Coast (for which SmartDwelling I was designed) which is frequented by hurricanes, then you really need to be able to close solid shutters over your windows to protect them from the storm. But how do you close the shutters once the window is closed? Southern European casements solve this problem by opening the casements inward rather than outward, but inward-opening casements almost always leak in a blowing rainstorm. This might be tolerable in the milder climate of southern Europe, but not on the Gulf Coast. Until now, the only choice was to close the shutters from outside the house... perched on a ladder for most windows. That’s why shuttered casements are almost non-existent there.

Until now, that is. One of the major epiphanies of SmartDwelling I occurred when I asked myself “if you can crank the casement sashes open and closed, why not crank the shutters, too?” Presto... we now have the superior weathertightness of a casement with the protection of a shutter that can be operated from indoors. But that’s not all. Notice how a casement on a crank can be opened to any position you like and left there? Well, now you can do the same thing with a shutter. As a result, you can aim the sash & shutter at the prevailing breezes, channeling air into the room. And if you open them slightly wider, where they don’t exactly line up like the ones shown above, then it literally creates a funnel shape to transform a small breath of air into a more noticeable breeze.

“That’s great,” you might say, “but why are you telling me this if I can’t buy windows like that today?” Because now we’re talking to a window manufacturer that’s strongly considering making them! I won’t reveal who it is until they’re committed to the project, but I’m really excited that this could happen quickly. As a result of this encouraging turn of events, I’m working to get the remainder of the futuristic components of SmartDwelling I on the assembly line, too. More later…

Invisible Things

https://originalgreen.org/blog/2009/smartdwelling-i---the-invis.html

Several elements of SmartDwelling I, published recently in the Wall Street Journal’s Green House of the Future article, are highly visible. Two of the more important ones, however, can”t be seen at all... at least from the ground. See the grey roof just to the left of the Tower of Wind & Water? Those are the hot water solar collectors that provide hot water to the entire house. See the blue roof covering the two-story porch? Those are photovoltaic collectors that provide electricity to SmartDwelling I.

Both sets of collectors are on low-slope roofs, so there’s no way you can see them unless you’re a long way from the house. They also occupy the entire roof... in essence, they are the roof. This means that even if you’re far enough back from the house to see the roof surface, you’re still unlikely to notice anything different.

I tried this approach first on a design for a Green Shed at Southlands, a DPZ project near Vancouver. Southlands is a place where all of the people living there will be able to get all the food they need from food grown on the property.

Contrast this with normal collectors which are usually designed for the perfect angle of maximum solar efficiency, no matter how hideous that makes them look on the roof. This attitude of getting the engineering exactly right with not a thought for design likely contributed to the demise of the first green revolution that began in the late 1960s and died in the early 1980s. Read this post to find out why.

SmartDwelling II

https://www.mouzon.com/blog/smartdwelling-ii.html

Wanda and I designed SmartDwelling II for a competition recently that we never expected to win. The competition was sponsored by two very respectable organizations which will remain nameless, but the program really disturbed us. It purported to call for a home in a hot climate (north Texas) that was both highly affordable and sustainable, but it was classic Gizmo Green, focusing solely on better equipment and materials, and inexplicably banning several passive measures. For example, it required 8' ceilings throughout although tall ceilings are essential in the deep South because they let the heat rise away from you in the afternoon.

I was disgusted with the program and didn't want to participate, but Wanda kept pushing, saying "why don't you use our entry as an opportunity to show what they should have been looking for?" So we decided to do the competition as a critique of the program in order to call attention to this completely backwards but very common approach to sustainability.

The two biggest "game-changers" that affect many other sustainability measures are things we call "Conditioning People First" and "Smaller & Smarter." Here's how Wanda and I accomplished these things in SmartDwelling II:

Conditioning People First

I blogged a few years ago on the Original Green Blog about an idea I call Living in Season. Briefly, the idea is that if you entice people outside, they get more acclimated to the local environment, needing less heating or cooling when they return indoors. I've proven this personally since moving to South Beach nearly 9 years ago, and there are other benefits, as you'll see if you scroll down in this post.

• dog run at left side doubles as driveway if there's no side street • Master Garden is surrounded by high hedges • Inner Court is shaded by a fruit tree

We did several things in SmartDwelling II to entice both the occupants and the neighbors outside. First, we designed the entire site as either outdoor rooms or passages… there's no standard lawn anywhere on the site (the lawn outside the fence is public property.)

Each outdoor room and passage has distinct uses. The Inner Court just off the Keeping Room is the outdoor living room. The Master Garden is a small, very private outdoor room just off the master suite where the parents can have a bit of time to themselves.

• fruit trees line left side of Kitchen garden • Green Fence at rear has espaliered fruit above vining veggies • raised beds in center radiate out from Tilapia Tank

The Outer Court (just visible above at the left end of the garage) is completely paved for shooting hoops and other activities requiring a solid surface. The Kitchen Garden at the rear of the site can replace a substantial amount of grocery budget with home-grown nourishment, helping make the neighborhood a Nourishable Place.

The edible landscape isn't confined to the Kitchen Garden, however. The Green Fence is similar in concept to the Green Wall in SmartDwelling I, and it runs all along the rear and right side of the lot has fruit trees espaliered on the top half and beans, peas, and other vegetables trained up below.

Edibles continue all around the house as well. The setbacks required by the city are narrow, and are often wasted because what can you do in a 5' strip of land except let the dogs run? Here, however, we use them as a linear orchard, with fruit trees all down the left side of the house. Oh, and that's the West side, so they also shade the house from the scorching Texas afternoon sun. The front yard is a bit of a flight of fancy. People rhapsodize about "amber waves of grain," so why not have a wheat lawn as shown here? If the residents would rather have vegetables, then we're beginning to learn how to grow them beautifully, so the neighbors won't mind.

We're not just trying to entice the residents outdoors, but the neighbors as well. If every home on a block gave some sort of Gift to the Street, then the street becomes a place more people want to walk. Anything we can do to enhance a neighborhood's walkability builds its overall sustainability as well. In this case, the Gift to the Street is built into a fence recess at the front gate. It houses a bench on one side, for a place to rest, and potted flowers to the right, for a bit of visual delight.

Smaller & Smarter

view of garage & Green Shed with roof removed shows how much

storage space can be recovered in stud walls

SmartDwelling II is only 1,043 square feet, substantially smaller than the 1,400 square foot program. It houses three bedrooms and two baths within this envelope by doing a number of innovative things. Clothes are stored in armoires rather than closets, saving roughly 4" per wall. It doesn't sound like much, but it really adds up. We carved into interior walls throughout the house, using the wall cavities as storage instead of wasting them. We used a dining booth rather than a dining room, saving a lot of square footage by seating people in a cozier setting. Go to a restaurant anywhere, and you can see how decisively people choose booths over open tables when given the choice.

Other Frugal Things

Building a smaller footprint starts many virtuous cycles. For example, smaller floor plans are much easier to cross-ventilate because they are small enough that you can give every room windows on at least two different walls, enhancing air flow. And light from two sides isn't just more beautiful, it helps to daylight the room so that you likely don't need to cut on the lights until evening. But we incorporated a number of other natural features as well:

The program required a front-facing garage, but we ignored this requirement for several reasons, chiefly because of the fact that buildings in temperate regions should be as long as possible East to West, reducing the length of the Western wall and increasing the Southern wall, where it's easier to admit the low winter sun while shading out the high summer sun. But a front-facing garage would force the house to be long North-to-South, dramatically lengthening the Western wall to the Texas sun. Front-facing garages also reduce the walkability of the street for several reasons, including the fact that houses with garage doors as major street features are notoriously less lovable. Because this house sat on a corner lot, we entered the garage from the side street. And as noted in a caption above, if this design is used in the middle of the block, a driveway can run down the right side to the Outer Court, which then doubles as a motor court.

The roofing is a major passive cooling device. Mill-finish 5V Crimp metal roofing was the predominant roofing material for many years in the South because it bounces roughly 90% of the sun's heat back up to the sky before it even gets into the building envelope. We've designed this vent hood similar to the Breeze Chimneys on SmartDwelling I: The fin turns the hood into the wind, so that the air flowing across it pulls warm air out of the house. It's sort of like a whole-house fan that doesn't need electricity.

There's more, of course. I'll have to do another blog post showing the interior innovations that haven't been mentioned here… there's some really cool stuff. But what about the competition? We were right: SmartDwelling II never stood a chance. The prime sponsoring organization apparently took offense at the number of program requirements we ignored, but I'm still happy Wanda talked me into doing it, because more of us have to start calling out the Gizmo Green for what it really is: a strategy that cannot deliver real sustainability on its own.

~Steve Mouzon, Jan 28, 2012, 1:00 PM

Appendix D

A Living Tradition

Book by Steve Mouzon, 2018

Synopsis from Book Description

A Living Tradition [Architecture of the Bahamas] is a richly illustrated description of the architectural traditions of the Bahamas over the past four centuries. But this is not just another catalog of architecture in paradise. Rather, it is a workbook, or "pattern book," that examines each pattern of architecture in detail, such as the proportion of a window, the slope of a roof, or the design of a garden wall. By doing so, it directs the design of new buildings that can become part of the centuries-long tradition of the architecture of the Most-Loved Places of the Bahamas. Until now, pattern books of our day were something akin to recipe books, instructing which details to use for each style of architecture. A Living Tradition re-thinks pattern books from the ground up. It is principle-based, not style-based. Those principles are based on the architecture that makes the most sense for the Bahamas, not a random collection of historical styles. And each principle is explained in the plain-spoken fashion of "we do this because..." One reason for building this way was to be sustainable. Originally (before the Thermostat Age,) traditional architecture had no choice but to be green, otherwise people would suffer or even die from weather and storm conditions. A Living Tradition explains the Original Green of each pattern that contributes to sustainability, re-infusing architecture with the green wisdom all our ancestors knew by heart. With this book, it's not just about style anymore. This second edition has robust new first and last chapters dealing with urbanism, and detailing the reasons why town-building is more resilient and more sustainable than resort-building. The Original Green is expanded with the four foundations of sustainable societies within sustainable places because even if the physical artifacts of a place are highly sustainable, the society could nonetheless fail within it if it doesn't keep these foundations strong.

Appendix E

Architecture for the Poor

Book by Hassan Fathy, 1968

Synopsis from Book Description

Architecture for the Poor describes Hassan Fathy's plan for building the village of New Gourna, near Luxor, Egypt, without the use of more modern and expensive materials such as steel and concrete. Using mud bricks, the native technique that Fathy learned in Nubia, and such traditional Egyptian architectural designs as enclosed courtyards and vaulted roofing, Fathy worked with the villagers to tailor his designs to their needs. He taught them how to work with the bricks, supervised the erection of the buildings, and encouraged the revival of such ancient crafts as claustra (lattice designs in the mudwork) to adorn the buildings.

Appendix F

Guastavino Vaulting: The Art of Structural Tile

Book by John Ochsendorf, 2013

Synopsis from Book Description

The first monograph to celebrate the architectural legacy of the Guastavino family is now available in paperback. First-generation Spanish immigrants Rafael Guastavino and his son Rafael Jr. oversaw the construction of thousands of spectacular tile vaults across the United States between the 1880s and the 1950s. These versatile, strong, and fireproof vaults were built by Guastavino in more than two hundred major buildings in Manhattan and in hundreds more across the country, including Grand Central Terminal, Carnegie Hall, the Biltmore Estate, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, the Registry Room at Ellis Island, and many major university buildings. Guastavino Vaulting blends a scholarly history of the technology with archival images, drawings, and stunning photographs that illustrate the variety and endurance of this building method.

Appendix G

How to Build a Small Town

How to Build a Small Town in Texas

Part I: The Place.

JUL 06, 2021

Of all the questions I get on Twitter the most common is this: “How do you build a town?” We know well how it used to be done, but these last one or two centuries we have forgotten how to do it (with only a handful of notable exceptions during the last century1). The other day I was asked again, but this time with a set of premises that made the question a little easier to approach. I have anonymized all the details but the general idea remains: four guys (friends) with money have bought a suitably large piece of land in Texas and now want to create a car-free human-scaled town2 of the kind that I am always writing about.

In this text I intend to set out the most bare-bone basic premises for how to start a good town, what is needed to build something anti-fragile3 and sustainable4 under the above mentioned scenario. I will go back to this text and edit it, add points, or discuss certain aspects deeper in future texts, especially those points that stimulate questions or controversy.

This is my first published long form. It is my general idea to write as little as possible while still getting the point across. I might delete this first attempt.

- Size and borders: “You can’t have a garden without fences.”

To create a human scaled town we first establish what is a good size, and this is simply one third of a square kilometer, or 82 acres, or 0.13 square miles. 80 acres was the upper limit for a good family farm in medieval England, and it is still the size at which the most flexible and efficient farms run, both modern and more old fashioned Amish family farms. It allows a town where no point can’t be reached on foot in 15 minutes, and it allows comfortable living for a population of 3000, which was considered the ideal size in medieval Europe: the upper limit of efficiency and comfort, productivity and harmony: more and you get crowded, less and you risk being without some important trades and activities. Even though the premise talks about a town of 600, we plan three centuries ahead for a maximum population of ca. 3000.

A good town (the urban) is clearly defined and set apart from the countryside (the rural). The suburban has no place here. Hence the town needs to be as clearly marked out and defined as the individual family lots will be: to here, but no further. For this purpose we will mark out land to be used as a wall, raised embankment, hedge, fence, moat, canal, etc. Some sort of edge which is not routinely nor distractedly crossed.

As for shape, I recommend a somewhat irregularly oval shape, near round in one extreme, or rice grain shaped in the other extreme, for the simple reason that the best towns and cities seems to be oval to some degree5. As far as possible the existing topography should be kept or even enhanced. Perfectly flat land is only popular with boring developers. So: no bulldozing allowed. Existing trees should be left and existing paths should be left in place (even when slightly inconvenient). New paths and streets should follow the contours of the land. Anything historic (an old campsite, an ancient grave or remains of an old farmstead) should be kept and protected and venerated. History is in short supply in new developments, and interesting stories can be woven around something as mundane as an abandoned old cart or well.

The oval (left) and the (Japanese) grain of rice. Good basic shapes for a town.

- Water, energy, food and connections: the needs hierarchy of towns.

Since the premise is Texas, and undeveloped land, I am imagining land that is more or less parched, but with short and intense annual rains that risk flooding the entire area. The town will be in a perpetual state of drought and need to be prepared for flash floods6. Hence cisterns, reservoirs, water harvesting will be vital, and whatever gets built, roofs will harvest water into private cisterns or ponds, and all streets will direct stormwater to overflow-proofed cisterns. An area the size of two or three football pitches outside the town will be devoted to flood protection and temporary storage of water. During most the year this land will be dry and a perfect spot for sports, barbecues, festivals, playgrounds, fairs and markets.

This arrangement should make the town self-sustainable in household water at least. Pumping groundwater should not be an option, it is simply not sustainable in an arid/semi-desert environment and Texans already know how to build and manage water harvesting infrastructure. There is no need to reinvent the wheel and spend tons of resources on piping in distant water.

There will be an urge to build each home optimized for air conditioning. Don’t. All buildings must be useful and livable even with the power cut. Hence, natural ventilation, strategically designed windows that open, etc. is necessary. Obviously you can add AC (Air conditioner) on top of that, but in no way should the town be dependent on AC. I don’t think a town can casually produce the energy it needs by itself (for that a far more serious effort would be needed), but even if the grid is cut, it should have enough to power food storage, basic lights and communications (WiFi etc.). This can be achieved with limited private and public PV (photo voltaic or solar power). For hot water, solar heaters are useful even in a Texan winter, and all homes will be equipped with fireplaces, wood stoves and chimneys.

Once you remove the need for heating, cooling and transport from a town’s energy needs, you are left with something that will easily run on limited solar (and the attached batteries) in case of a grid failure. This will also save the town and its people large amounts of money even in the near future.

For food, the town should not spare any effort to be self-sustainable. Food items are also a prime export product, especially high-end refined items (exporting raw materials/food isn’t a good use of resources). It provides jobs and income and is a sure way to draw tourists. For this purpose there will be no lawns, but plenty of gardens, orchards, street side herbs, roof top apiaries and flowers to feed the bees that inhabit them. The rural area (the “market garden zone”) surrounding the town out to a radius of one mile should be devoted more or less entirely to food production in some form, and it should be farmed primarily by the people living in town on a professional or hobby level (either one is fine: create the best allotment system in Texas!). The second belt, is the farm zone. Here I would recommend, if not enough farmers could be found, to offer the land at good prices to Amish families to farm. 800 acres is enough for 10 farms. They also have the expertise to run a farm in any sort of energy crises. The rule of thumb is that only people who live directly off the land should live in the rural area (the “farm zone”).

Inside the town basic facilities for food processing should be found. From feed and dairy refinement to meat processing. People should be encouraged to plant espaliered fruit trees on every suitable south facing wall. Poultry, pigs and rabbits should be kept, not only for meat, eggs, but also to produce high quality fertilizer for the poor soil in the area. And this goes for humanure7 as well. Pesticides and chemical fertilizers should be completely banned from the start. Water should be treated organically and as low-tech as possible, on site.

A good “code-hack” for any small town was developed in Seaside, Florida: “one 14x14 feet area of a lot has no height limitation”8. This will spur people to build towers and spires, which are useful for housing bats and pigeons which will help in pest control (pigeons are also an unbeatable supply of food). Some space in the town itself should be reserved for food production: dovecotes, commons for grazing, etc. A small town like this needs no parks, so instead institute seed gardens (small gardens used only for producing seeds) of vegetables and herbs. Encourage people to keep flowers (to help honey production): consider instituting a program where each square foot of flower pot space gives you a certain weight of honey from the public or private apiary.

Ideally you want to build a new town in a region where there are already people present, near larger cities or along a “necklace” of small towns. This makes it easier to attract citizens, and it also makes the town less isolated, more easily connected to outside markets, tourism etc. but in this scenario the land is marginal and a bit far from towns and airports. Hence, save space for a convenient and scenic (you can’t do fast at this scale) rail or canal or river ferry connection to the nearest larger town. It will raise the value of the town land itself and everything it produces will have a better access to a market (especially perishables). It is also a great way to bring tourism into the city without having to provide parking.

It is possible to build isolated cities but the chances of succeeding is so slim I would not recommend it. Decide from the beginning where you want a possible rail station, by the gate? Inside the town? Through the town? It is easy to prepare the ground now, rather than wait until it is all developed and built up.

- Materials and harmony.

All materials used, as far as possible, should be of local origin. In Texas that means the town will be built from rammed earth, adobe bricks, some fired bricks or stone. No concrete, vinyl sidings, clapboard (not ideal in an arid town environment anyway), plastic etc. Before anything gets built, a pattern book9 for the town must be developed that should have a few very basic buildings types for new residents to easily build and that fits in anywhere in town. A color pattern will be developed using locally accessible earth tones and pigments (if the local geology provides some odd hue of green or yellow here’s a chance to make the town stand out from the beginning). Official or public buildings should be set in a specific color to create a coherent pattern for the town. I recommend bright yellow and white trimmings for this purpose.

- The problem of undeveloped and vacant lots.

In the beginning, especially in a town planned for 3000 but only housing 100-600, there will be plenty of empty lots. These should still be managed and walled or fenced, with the understanding that they will, sooner or later, be built upon. These “gaps” can be filled with low walls and contain gardens and playgrounds until they are sold or developed. Fast growing trees can be grown on empty land and used as energy or raw material.

Tournai in modern Belgium. Look at all the green spaces, imagine the fresh air, the invigorating call of roosters in the morning, the scent of herbs and flowering orchards in the early summer breeze!

- Who will live there?

Obviously the town will need to generate a working income, so lots will be sold to the highest bidder, but you will also want to reserve lots for the people who matter to the town itself. I.e., you need things like a parish house, a dentist (save an excellent spot in the town center to offer at low cost to whomever decides to practice dentistry there), a schoolmaster, a clinic, a grocery store (at least) etc. Your first and most obvious potential clientele will be the builders, plasterers, masons, well drillers, cistern makers, ditch diggers, hod carriers, carpenters, plumbers, glaziers, electricians, wifi technicians, who are actually building the town, so you will want to offer them a chance to live there, affordable, within their means. Let the people who contribute and have skin in the game have a first go at acquiring land. The surveyor who surveys his own home will work twice as accurately, the carpenter who builds for himself will work twice as hard.

You also want craftsmen and small business owners to relocate to the town and they will need workers. All buildings must be owner occupied. You do not want a town of renters or absent landlords. Set lots aside to develop “guest houses”, inns, small hotels or rentable properties for short or long-term visitors and guests. Reserve the most valuable street front lots to people who want to run stores, eateries and other businesses.

Without motor vehicles and endless power flowing through the socket, this will be a remarkably quiet town. The loudest noise you will hear on a typical day will be children playing or a conversation between neighbors in the street. And so it should be.

- Build to the edge of the lot

Keep the lots small, and all buildings aligned right to the edge of the lot facing the street, leaving backyards and courtyards, common or private, and walled gardens on unused space.

All buildings in this water color of an Italian town are built to the edge of the lot and we can only see the front elevation (and one of the sides of the building on the far left). This saves us money because we only need to consider the decoration of one side, or maybe two, in the case of smaller humbler town houses. If we want to add to the house later, it is easy to add more rooms on the back, taking some space from the often ample courtyard or backyard.

- Personality, neighborhoods, and character.

Even a small town needs neighborhoods, and neighborhoods need a character and “color” or personality of their own. Since there are four guys building this town, assign a quarter each for their personal whims and quirks. One guy might have a thing for public wall mounted fountains, so he asks all the builders there to install them. Another might have a thing for the color purple, so he asks all buildings to use the color in some way for doors or trimmings and flower pots etc. This sounds whimsical but it is vital: most people love the quirky and detest the bland.

- The Story, the founding Myth.

Any town needs a story or a founding myth, and if it does not, let’s make one up10. The easiest way to make a new development, town or building fit in is to make it look like it has always been there. The newest building on the block should look like the oldest. In the case of Texas, this means the town will be built to a Mission, Spanish-colonial, or German-colonial style (or a mixture of these). It should look like it was founded and laid down in 1667 or 1746, not 2022. People will call pastiche or Disneyland on this, but don’t listen to them: if you use genuine materials and colors it will only take a few years to mellow in and look like it has always been here.

- Build the least valuable lots first.

Don’t develop the best lots and the best locations first. Save them for later. In the meantime, “pop-up” stores and light movable homes and buildings, simple stick frames place holders, can be placed on the prime lots, to be replaced by more permanent constructions as needs and wishes becomes apparent. Here’s a chance to build the funky saloons, the charming post office, the rows and rows of shops and cafes that makes a town a fun place to visit without committing for entire generations. If they do great, make them permanent, if not, move them out, replace them, experiment.

The same thing applies for street furniture: fountains, benches, water troughs, hitching posts etc. Build fast and simple place holders, and see which ones are used and loved: make them permanent. The ones that no one cares about, remove or change or replace. Rome wasn’t built in a day.

Also remember the golden rule of place making: when building anything, build on the least attractive part and improve it while keeping the views of the more beautiful parts intact.

- Public space.

Texas is hot and sunny so streets should be relatively narrow and main streets should have covered walkways or porticoes (look at Bologna for a famous example, or old Havana with its tarpaulins shading the streets, or old Singapore with its covered merchant sidewalks). Useful street trees should of course be planted, as many as possibly under the limitations of water and rainfall, with a good mixture of flowering trees, shade trees, evergreens and fruit trees, both male and female, with an emphasis on useful native trees. Give each neighborhood its own square and make the entrances gated or arched, and the streets offset (i.e. no street intersects another). Each neighborhood or even set of homes should have a pocket square11 adjacent. The town itself should have a central square12 (even if it does not have to be in the center of the town itself: it can also be in front of one of the main gates or up on the hill or down in the hollow), with some sort of trees and water feature if possible. Water should be available in the form of fountains and faucets, water troughs and wall mounted fountains as far as possible almost everywhere.

- A grand entrance.

Just like the front door is the most important part of a home or building in how it interacts with its neighbors and the street itself, so should the town have a dignified entrance. A gate or portal or archway or flanked street or special pavement etc., something that tells the visitor “this is our town, we live here, and we are proud of it!” You really can’t go over the top here. The gate can be lockable if wished, or open at all times. It can be freestanding or built into homes or a building in itself

By the City Gate by Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847-1928)

- How to live without cars.

The most common response when I claim we should keep cars out of cities is “what about emergency services?” Having a single ambulance in town is no problem, and hopefully it will be rare to even see it on the streets. Same with firefighters. Long hoses and mobile pumps and ladders are good enough for a town with no buildings over two or three floors. Still, a small ladder engine can be kept in town if deemed necessary.

A town without cars is more accessible for everyone, including the handicapped, wheelchairs, etc., especially for the two large groups of people who can not drive even under the best of circumstances: the elderly and the young.

There are many ways to move goods and materials, pianos and washing machines, that do not include moving vans and trucks (even though obviously exceptions can be made for these purposes), cargo bicycles, wheelbarrows, hand powered cargo rail etc. For residents who are temporarily unable to leave their homes a human-scaled walkable town is the perfect setting for quick and local delivery services, or just plain charitable spirits and “helping each other out.”

But where will people keep their cars? Outside the city boundaries somewhere.

- To grid or not to grid.

I have this pet theory that you can tell how free a city is by how irregular its street pattern is. Grids are great for managing traffic, and nothing else really. A town with an irregular street pattern is far more charming. If you think of a town as a home, the streets in a gridded town are corridors, not useful for much anything, but in a town with an irregular street pattern they become rooms, or real places. If you have a grand building, let it stop a street (in urbanism this is sometimes called a “terminating view” or a “focused street”). If you have several beautiful elevations in a row, curve the street to properly show them to the pedestrian (it can be hard to take in a building if you are next to it on a straight street or lot line). Consider also if streets are always necessary. Sometimes it can be better to divide buildings and blocks be series of interconnecting pocket squares or little plazas.

Consider what a street can be good for apart from just foot traffic. Is the street narrow enough to shelter from the sun? Can the south side be covered to provide a place for shops or outdoor seating for a cafe? Is there a convenient corner to stop and fix a flat tire or water a thirsty mule? And what about when you enter a new street, is the “scene” well set? Does every turn and every corner fulfill its potential to present a charming or attractive scene?

I hope to add to the themes in this text and also follow it up in a Part II: The People, where I will focus on how to set things up to maximize the chances that an organic, real, honest, community, forms. This Substack will be open to free subscribers for a while. I wish to thank the Substack staff that have kindly reached out to me before and after registering.

Léon Krier is responsible for most of them.

Defined here as a town that is completely accessible and useful on foot or by hand and with human or animal muscle power, both in terms of size, space use, and materials (for example anywhere in the town is reachable on foot within 10-15 minutes, and buildings are not so tall so that they can’t be used without elevators/lifts/escalators etc.).

Defined here as the way Nassim Nicholas Taleb uses the word: that which benefits from stresses and shocks.

Defined here as: “a place or practice that can keep going even after someone pulls the plug or disconnects the grid.”

In other cultures square or rectangular towns exists, as does circular, but according to the premises for this scenario let us go with something vaguely medieval and Western.

The most common cause of death in the desert is drowning (flash floods).

Humanure, i.e. human waste, nightsoil. A valuable resource. A good book on this is Holy Shit: Managing Manure to Save Mankind, by Gene Logsdon. Recommended reading.

I tweet about this here:

A book with plans and layouts and elevations of acceptable or recommended designs along with color samples and materials guidance. “Anything in the pattern book gets an automatic building permit: anything that is built and fits, gets added to the pattern book.” See historical English and U.S. pattern books for examples.

A book that tells of real world examples of “made” up founding stories is Charleston Fancy: Little Houses and Big Dreams in the Holy City, by Witold Rybczynski. Recommended reading.

A pocket square may or may not be a made up word or jargon. Nevertheless, here it is defined as a square that is roughly of the same size, or smaller, as the building lots that surround it. A proper square is usually larger than the surrounding buildings (i.e. it serves more than two buildings). Stockholm’s Gamla Stan is a good example of a town with nice pocket squares.

A good guide to the proper dimensions of a square or a public plaza is given in The Art of Building Cities: City Building According to Its Artistic Fundamentals, by Camillo Sitte. However, there hasn’t been a decent public square built since the 16th century, so please be prepared to sit down and really work on this part of the city. If you can get it right you will have created something not seen since the Renaissance.

Appendix H

On Copying Old Designs

@WrathofGnon

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1148825660963426309?t=Ifv9p9V7sJb6d_X8e_gCYQ&s=19

“Thanks to Louis XIV we have a very good idea of how European cities looked in the 17th-19th centuries. About 260 models of cities and fortifications were built up until 1870. 100 of them have survived. We can start copying the best of these if we want to build sustainable cities."

Note: Leavenworth, WA became a destination by doing this in miniature

Appendix I

Duplication Through Replication - Leon Kreir

https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2019/5/27/do-you-want-to-know-what-works

After infill, a mature city has two options for growth. Expansion or duplication. He provides two sketches to illustrate the point; the first of a technically-administered city that has become obsessed with growth. Krier calls this “Vertical & horizontal overexpansion”—the vertical and horizontal simplification of the city to constituents of a growth model.

The other Krier sketch he calls “Organic expansion through duplication,” and he even throws in the word “organic,” which I would correlate to “complex.”

Appendix J

A Town Well Planned

Blog Series by Alexander Dukes, 2017

https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2017/3/13/a-town-well-planned